On Memorial Day weekend, I plan to take on a wild challenge — the Capital Backyard Ultra.

For those who are unfamiliar, a Backyard Ultra is a distinctive type of ultramarathon. The course is 4.167 miles (6.706 kilometers for my friends in Europe… and pretty much the rest of the world outside the U.S.).

Why 4.167 miles? Good question. If you complete 24 laps, you’ve run exactly 100 miles — a milestone of legendary status in the ultra world.

Here’s how it works:

- You have one hour to complete each 4.167-mile loop.

- If you finish the loop in under an hour, the rest of the hour is yours — eat, stretch, change clothes, go to the bathroom… whatever.

- But when the bell rings at the top of the next hour, you have to be back at the start.

- Then… you run the loop again, and again, and again.

- Until only one runner remains.

Yeah — it’s that kind of race. Welcome to the strange and amazing world of backyard ultras.

The Format: Simple Rules, Brutal Outcome

The Backyard Ultra format was created by Gary “Lazarus Lake” Cantrell — the mastermind behind the infamous Barkley Marathons. It’s deceptively simple:

- Runners must be in the starting corral when the hourly bell sounds.

- They get a warning bell at 3, 2, and 1 minute before each start.

- No outside support is allowed on the course.

- Between loops, you can eat, hydrate, nap, and even get a massage — but once that bell rings, you’re back on your feet.

- Everyone except the last runner is a DNF (Did Not Finish).

And yes, that’s technically a failure — but one you wear like a badge of honor.

How Far Can You Go?

You might be wondering: What’s the farthest anyone has ever gone in one of these?

The current record (as of 2025) is an unbelievable 116 loops — 483 miles (777 km) — set by Łukasz Wróbel at the Legends Backyard Ultra in Belgium. Go ahead and pick your jaw up off the floor.

Why Would I Do This To Myself? The Surprising Advantages

It’s a good question, and I’m sure to ask myself that question when I’m out there. Unlike traditional races with fixed distances and cutoffs, backyard ultras level the playing field. Runners of all paces toe the line together, and it’s not always the fastest who win — it’s often the smartest, most resilient, and best-prepared. The hourly loop format allows for regular rest, fueling, and gear adjustments. There’s also a strong sense of camaraderie; everyone starts every loop together, and the last person standing doesn’t “win” in the usual sense — they just outlast everyone else. It’s less about speed and more about grit, patience, and community. For me, the ultra-running community is eerily similar to the diabetes community in that way.

What Makes This Race So Tough?

Backyard Ultras challenge you physically, yes — but more than anything, they’re a mental game. Just a few of the many things you have to consider:

- Night running

- Mental fatigue

- Pacing strategy

- Nutrition and hydration

- Tent setup, gear organization

- Weather variability (heat during the day, cold at night)

- Bathroom logistics

- Transition timing and efficiency

- Sleep strategy (if you’re lucky enough to get a few minutes!)

- Foot care, electrolytes, sodium intake, and thermoregulation

Now Add Diabetes to the Mix

On top of all of that, I have type 1 diabetes. That means I also have to plan for:

- Site prep, placement, and maintenance

- Insulin-to-carb ratio adjustments

- Correction factor changes

- Managing highs and lows

- Backup insulin and CGM supplies

- Batteries and connectivity issues

- …and backup plans for my backup plans

It’s a lot. But I’ve been training hard for six months to get ready — physically and mentally. I follow a two-week training cycle: one high-mileage week (60–70+ miles), followed by a recovery week (35–40 miles with cross-training). I’ve done multiple night runs using the same format of (roughly) 4 miles every hour to simulate the race.

Tech That Helps: the Dexcom G7 and the Omnipod 5 in Exercise Mode

I use the Dexcom G7, and the Omnipod 5. The Activity Mode for the Pod has been a game-changer. Here’s how it helps during activity:

🔹 Higher Glucose Target:

Sets a target of 150 mg/dL instead of 110 mg/dL — lowering the risk of insulin-triggered lows.

🔹 Less Aggressive Insulin Delivery:

Reduces automatic corrections and basal rates to help prevent hypoglycemia during exercise.

🔹 Smarter CGM Integration (Dexcom G7):

Still uses CGM data but responds more conservatively when glucose levels are trending down.

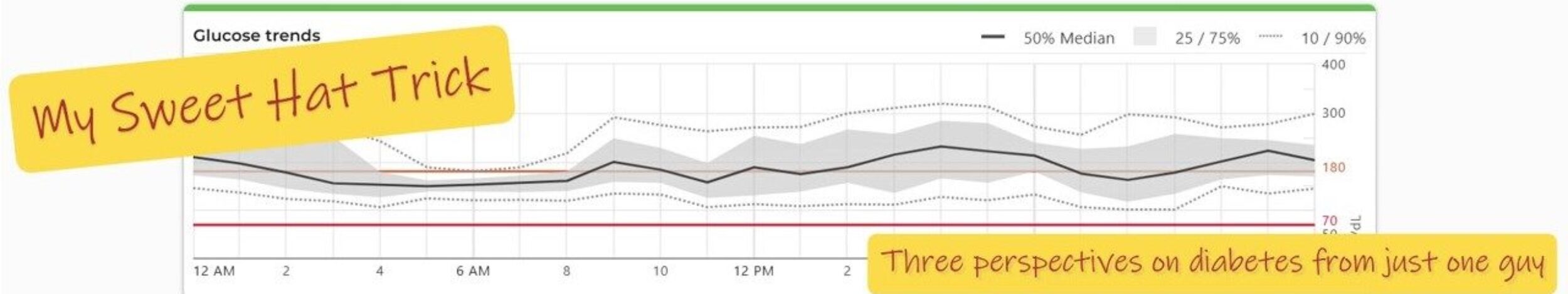

The insulin plan? Less is more. Activity boosts sensitivity, so I’ll need to cut mine dramatically. The Pod will already be in activity mode, but I’ll also need to consider my bolus calculations. My usual carb-to-insulin ratio is 1:15, and my correction factor is 1:28. These ratios increase by a factor of three when I exercise, but I tend to do the math in my head – a 4-unit bolus for 60 grams of carb before I run becomes 1.0 units. For the race, I’m worried I’d get tired and forget to do the math, so I will plan to make the changes to the bolus calculator manually: increase the carb ratio to 1:60 and the correction factor 1:112, higher ratios. My major concerns are that when training, my BGs were a little higher then i would want, and I thought that might be becasue I’m used to running 9 minute miles in trainingm, not 13 minute miles. but I’m also concerned about insulin stacking which happens wher you take multiple boluses. I’ve practiced with these in training, and they seemed to hold up. Of course, at some point, it becomes jazz improv based on vibes and blood sugar trends.

My fueling plan was to eat roughly 80g of carbs an hour (400 calories)—and yes, that’s a lot of eating. I packed for every craving profile: sweet, salty, chewy, crunchy, cold, hot, regret-inducing. Think cookies, candy, fruit, chips, potatoes, and good ol’ chicken soup. If you walk by my tent, you’ll think I was catering a children’s birthday party and a tailgate.

What’s Next?

I’ll write another post soon to share how it all turned out — what went well, what I learned, and how diabetes factored in. Stay tuned.

Until then, if you ever wondered what it takes to line up for a race that doesn’t have a set end… now you know. now.