Ice bandannas, Bluetooth miracles, and one very stubborn blood sugar

Last Saturday, I ran the 12-hour race at the PA Run Trail Jamboree. A running festival held in Newmanstown, PA. It was my first race since the 6-hour Trail Fest, and I was eager to put everything I’d learned into action. There were some real wins this time around… and a few “learning opportunities” (ultra-runner speak for this part was kind of a disaster).

Conditions & Course

The weather cooperated this time—lows in the mid-70s and a high of 81°F. But with 59% humidity, it felt about five degrees warmer. Welcome to summer racing: it’s not just running, it’s also a light simmer.

To deal with the heat, I used a favorite ultra-runner trick: a DIY ice bandanna. You fold a bandanna, sew it to create a big inner pocket, stuff it full of ice, tie it around your neck, and instantly become slightly less miserable. The ice melts while you run, but keeping the back of your neck cool helps your whole body chill out—literally and figuratively.

The course itself was a 3.4-mile loop. The goal? Run as many loops as possible in 12 hours. Any lap completed after the 12-hour mark didn’t count, which added a little extra strategy (and a lot of muttered math) to the day.

The trail was a mix of single and double track—roots, rocks, grassy fields, and some dirt and stone roads. The website claimed it “wasn’t technical,” which is adorable. Each loop had 463 feet of climbing, adding up to over 5,000 feet of elevation gain. In other words: “not technical” is a relative term.

Diabetes Strategy

So let’s get down to the nitty-gritty, the T1D talk

In past races, my phone battery died, which meant no phone = no bolusing = no snacks = no fun. A quick fun fact about your cell phone: when your phone has a weak signal, it hunts for towers like a lost puppy, draining the battery fast. And since there were few cell towers in my area (similar to where I ran Trail Fest), the phone would have been working overtime to find a signal. Since both Dexcom and Omnipod rely on Bluetooth, I turned cellular off completely. It worked beautifully—my phone sipped power like it was rationing for the apocalypse. Win #1.

I also had connection issues at Trail Fest. The Omnipod app kept dropping the Dexcom signal, and my Apple Watch was doing the same. Due to battery issues at Trail Fest, I left my phone with my gear for the middle of the run. This time, I kept the phone on me the whole race and simplified the watch setup to reduce interference. It worked—everything stayed connected all day. Win #2.

Three hours pre-race, I had oatmeal—enough time for the bolus insulin to clear before the start. Then I multiplied my bolus settings by 4 :

- My carb ratio went from 1:14 → 1:56

- My insulin sensitivity factor: 1:28 → 1:112

- My BG targets: moved to 150 mg/dL

I also switched my Omnipod to Exercise Mode two hours before the start. The plan: bolus hourly for the carbs I was eating. And I was pumped to try Dexcom’s new photo feature on the app, because taking pictures of trail snacks mid-ultra is peak diabetes-tech nerdery.

Race Nutrition & Execution

For laps 1 and 2, I bolused for my carbs. But by lap 3, I had some insulin on board and got a little gun-shy with bolusing. I skipped the bolus… and then I just never bolused again. It was….AMAZING! I almost cried. (Although it may have been the cramps. Or joy. It was a blurry moment.)

The pump just worked. My blood sugar stayed steady. It was a dream. Kudos Insulet. You Rock.

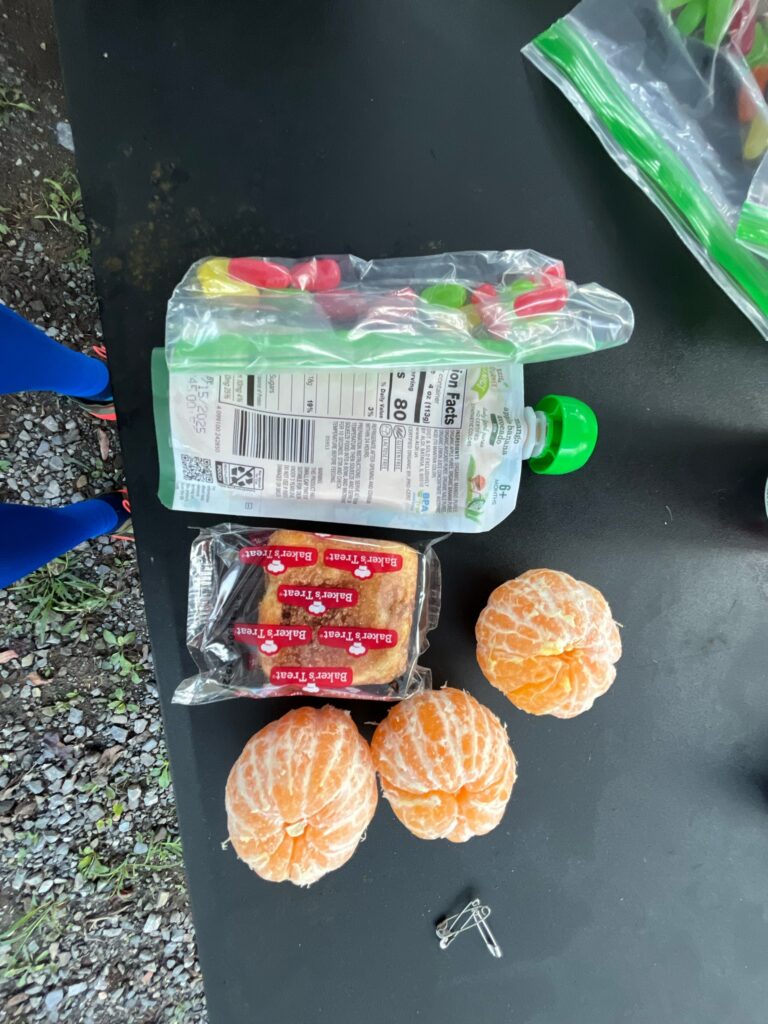

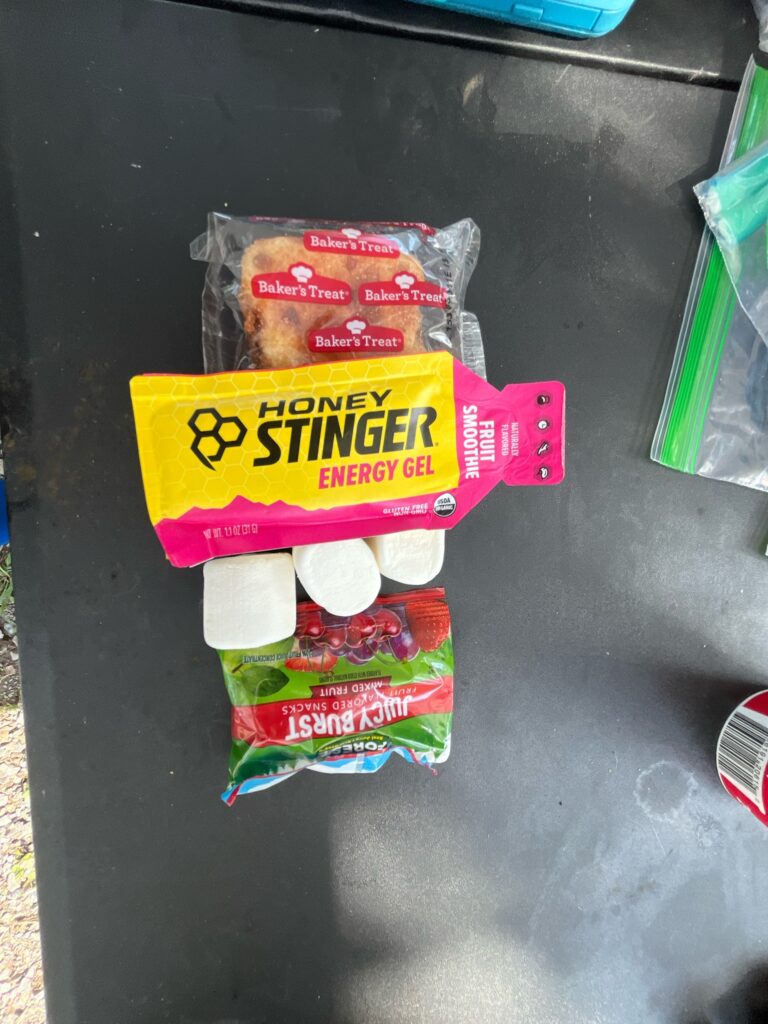

Dexcom’s photo feature was great, too. I’d tested it before the race and knew I could edit the carbs later, so during the run, I just snapped quick pics of my fuel and kept moving, figuring I could add the carbs in later when I wanted to analyze things.

The Omnipod and Dexcom G7 stayed on well. I used a combination of Skin Tac H and Skin Grip (picture is taken after I took these off) and had no problems with adhesion.

I held back in the opening laps, then picked up the effort mid-race. While I did slow a bit, that was mostly because I was spending more time at my tent between laps. I made a rule: don’t sit down—because once you sit, your brain starts negotiating (“What if we just stretch for a while… like, an hour?”).

By hours 6 and 7, I started running the numbers in my head. If I wanted to squeeze in one more lap at the end, I had to streamline transitions. So I stopped doing anything that was not absolutely needed, which was everything except food and drink. By that time in the race, I was eating the same thing every time, so I even skipped the photo for the Dexcom app. I even switched to the race’s sports drink instead of mine. First time I tried this? I knocked three minutes off of my stop. Game changer and Game On.

The Crash

And then… things got rough. Like the extra grit (basically the roughest) sandpaper rough

My BG had been trending down for the last two or three laps, not a huge drop, but in retrospect, something I should have identified and done something about sooner. Then on the last lap it went into full crash. mode. My blood sugar hit 64 mg/dL. That number normally wouldn’t phase me, but when you’re eight hours into a race, it feels like the 30s.

I was hot, dizzy, and dry-mouthed. The bugs swarmed me because I had slowed to a walk; they weren’t biting, but that was probably because my blood wasn’t very sweet ( A low glucose joke – funny right?). I ate the 55g of carbs I’d planned for… nothing. Then I added another 90g. Still no lift. My blood sugar was in stubborn toddler mode: refusing to respond, ignoring reason.

I staggered into the start/finish area and sat down. I just needed to stop moving. I had gotten to the point where the muscles were using the glucose faster than my body was absorbing it, and when you’re in that kind of spiral, you just have to stop.

After my sugar came back up, I took stock of where I was. By the time I was ready to go again, I was in 4th place. I could have gone back out. But because of the low, I was in a fragile mode, and a second one could come just as easily. Knowing I could have a second low as easily as the first convinced me to stop. If it had been soreness, fatigue, or heat, I might’ve pushed through. But I was here solo, without a crew or a pacer (something that the other runners had)—I had to be smart. These races are hard enough. No need to turn one into an emergency.

Plus, I still had to pack up my gear, drive home, and eat like a horse that just plowed a cornfield.

The Aftermath

The next morning, I checked the results. The 11 laps came to about 38.5 miles; I won my age group and got 6th overall. Not bad for a guy who dropped out with two hours to go. The winner ran 13 laps—totally within reach if I’d been able to push. So yeah, that stings. But I made good decisions. I didn’t push past the brink. And by Tuesday, I felt human again. I’ve even logged a few short runs since.

Final Thoughts

This race gave me a lot to be proud of—and a few things to work on. Managing type 1 diabetes during an ultra is like balancing on a tightrope with juggling pins, a hydration vest, and 12 kinds of carbs in your pockets. It’s never perfect. But this time, I hit a lot of the marks.

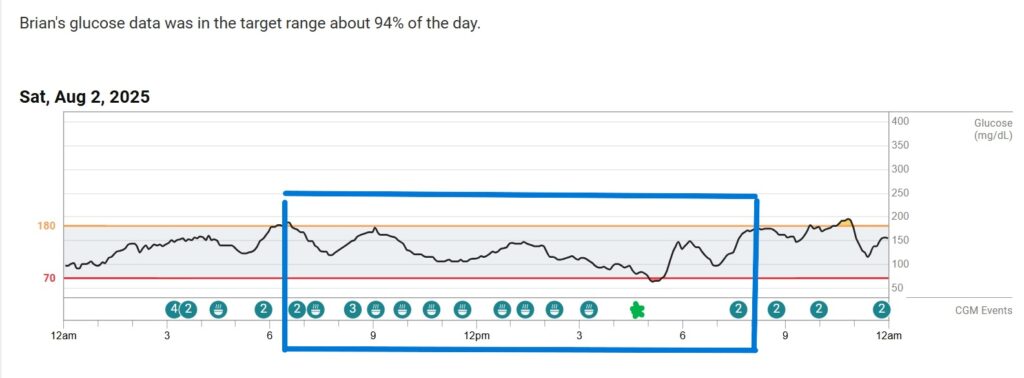

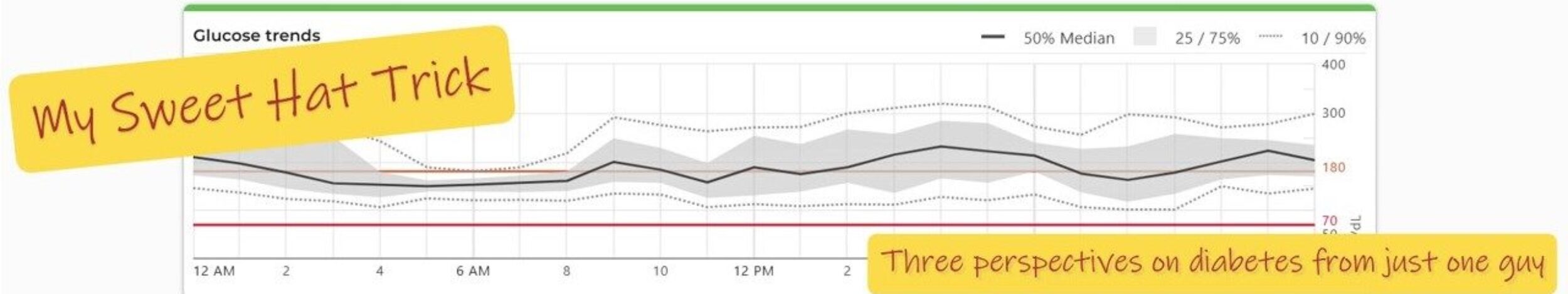

Overall, my blood sugars were great (I highlighted the portion of the day in blue, and made a mark where I had eaten but not marked in the Dexcom app). Sure, I fell off a cliff, but that can be identified and corrected. Now it’s about learning from the cliff, fine-tuning the setup, and showing up smarter next time because there will be a next time.

Cool post Brian. A lot of good insight! Best of luck.