There’s a reason why hot chocolate and sugar cookies go so perfectly with snow. And it’s not because Nestlé runs a secret subliminal campaign that makes you grab cocoa mix along with the bottled water and rock salt when you hear a snowstorm is coming. (Although that would be pretty impressive.)

It’s because if you’re glucose intolerant like me, you’re going to need all of those carbs, and probably a whole lot less insulin when you’re out exercising in the snow.

Because exercise changes everything.

I’ve said that before, and I’ll say it again. Exercise is amazing, not just for overall health, but because of the way it lets your body use glucose without needing much insulin at all. When muscles are active, they pull glucose into cells through pathways that don’t rely on insulin. Add just a little insulin on top of that, and suddenly you need far less than usual for the same food.

That’s why you can reduce your breakfast bolus if you’re heading out for a walk afterward. Or why insulin needs can stay lower for hours after a workout.

And let me tell you how that played out for Owen and me on this snow-filled Saturday.

4.0 Units + Exercise = 1.0 Unit

The day started like a typical Saturday. I had just finished working out downstairs when I heard Owen pop out of bed. My two older kids were still asleep after being up late the night before.

As Owen bolted into the living room, I peeked out the window and saw that we’d picked up another inch of snow since I’d last checked. I knew exactly what was coming.

“Do you want to go play in the snow, Owen?” Like I even needed to ask.

“Ohhh Yeah!”

So the Kool-Aid Man and I had to make our plan before breakfast. I knew he’d want to head outside the second he finished eating, which meant we needed to lower his breakfast bolus.

Owen is incredibly insulin sensitive when he’s active. His usual morning ratio is 1:24, but when he’s outside playing hard he’s about four times more sensitive, probably even more with the snow.

So I eyeballed it (yes, you read that right) and ended up giving him 1 unit. That’s right. One measly unit.

Then he prepared to head outdoors, with all the required winter paraphernalia. Mittens—check. Boots—check. Hat—check. None of it matching of course, but for a ten-year-old, that doesn’t matter. Out he went.

For me, my morning ratio is 1:14. I’m not as sensitive as Owen with activity, but I knew I’d be working hard. I went old school and made an educated guess: 1.5 units.

I set a timer on my phone for 45 minutes just to see where things were headed, then out the door I went. Then it was time to go to work.

Owen built snowmen. I shoveled.

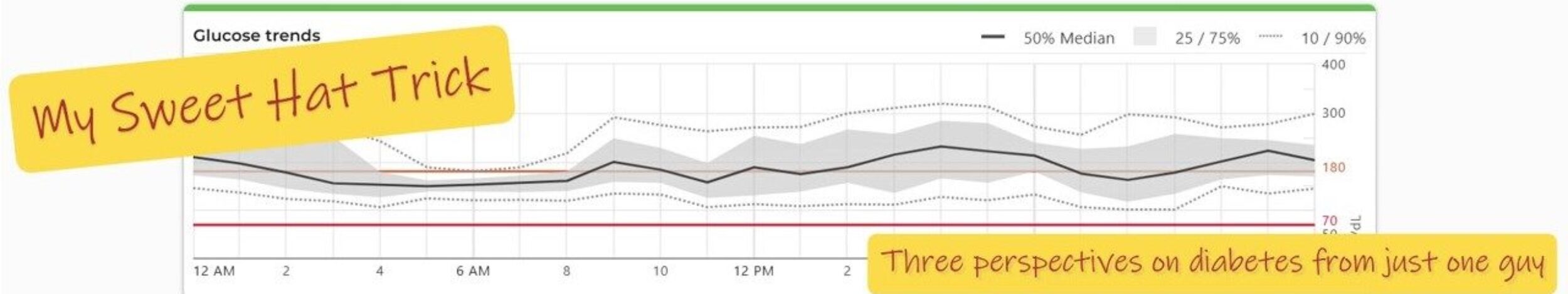

At the first check, we’d already seen the spike from our syrup-infused pancakes and were holding steady in the low 200s. So far, so good. I reset the timer.

By the next check, we were both trending down, very slowly.

At the following check? Not so slowly. A more appropriate word would be crashing.

Hot Chocolate, Cookies, and Pit Stops

This part was planned.

The night before, I had baked a batch of cookies. While Owen peeled off his snow pants, I made hot chocolate with marshmallows. So many marshmallows.

We stayed inside and watched part of Elf (thank you, streaming), and once our blood sugars started to rebound, we suited back up and headed outside again.

From there on out, Owen and I operated like Formula One race cars, making required pit stops; rolling into the house every 30–45 minutes, shoving a cookie or marshmallow into our faces, and heading right back out.

No lunch. Just a lot of cocoa. And amazingly, no additional boluses while we were out.

Snow.

Movement.

GLUT4 transporters doing their thing.

Minimal insulin.

Maximum joy.

We kind of had a backwards Nestlé commercial. Instead of hot chocolate after being outside, we had it beforehand—and repeatedly. Nestlé would’ve been thrilled.

The Diabetes Educator + Dad Takeaway

Snow days remind me of something I’ve known professionally for years, but feel most clearly as a parent:

Insulin dosing doesn’t happen in isolation.

Food, movement, temperature, excitement, and duration of activity all matter—and sometimes the “right” dose on paper is wildly wrong in real life.

That morning, the math said more insulin.

Experience said much less.

And experience was right.

What made the day successful wasn’t perfect glucose numbers. It was anticipating movement, respecting how powerful exercise really is, being willing to underdose—and most importantly, letting a kid be a kid in the snow.

That’s not just diabetes management.

That’s living.