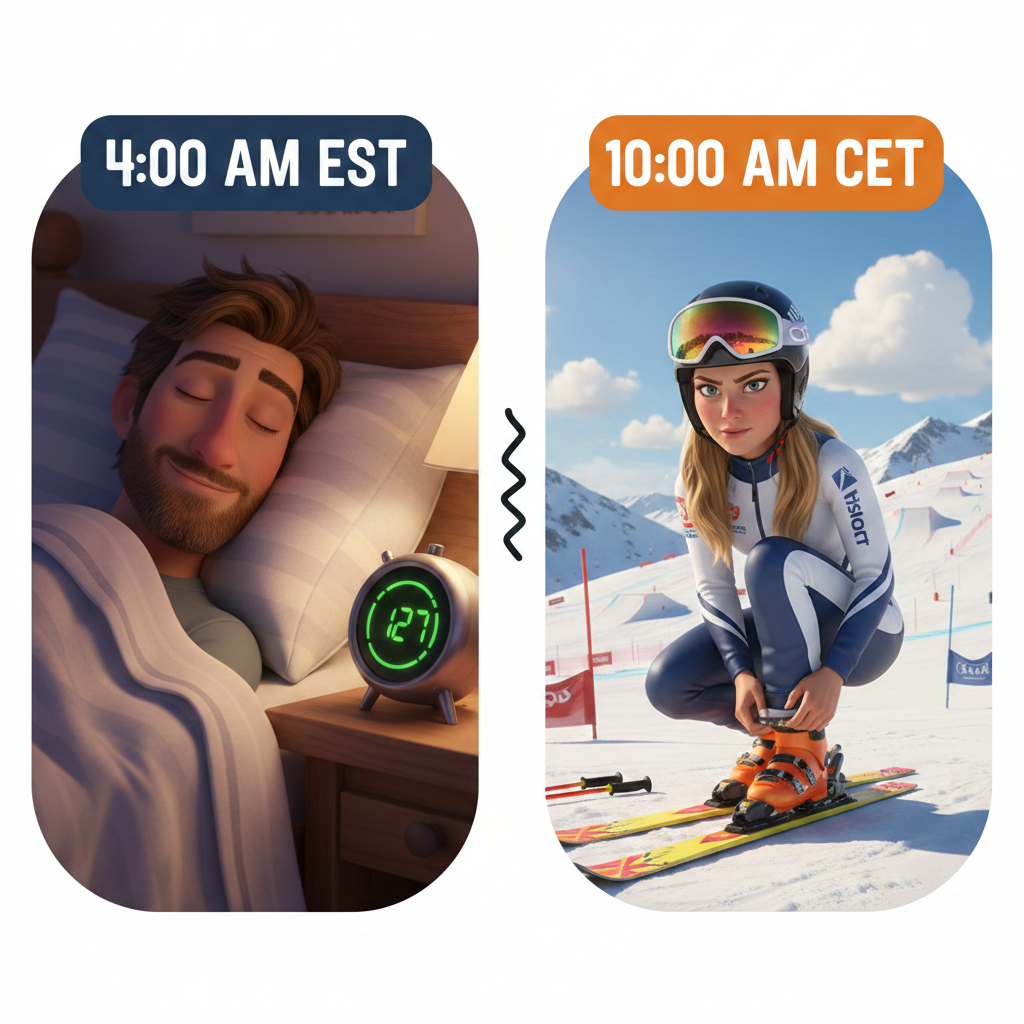

At 4:00 a.m. EST on February 20th, most of North America will still be asleep.

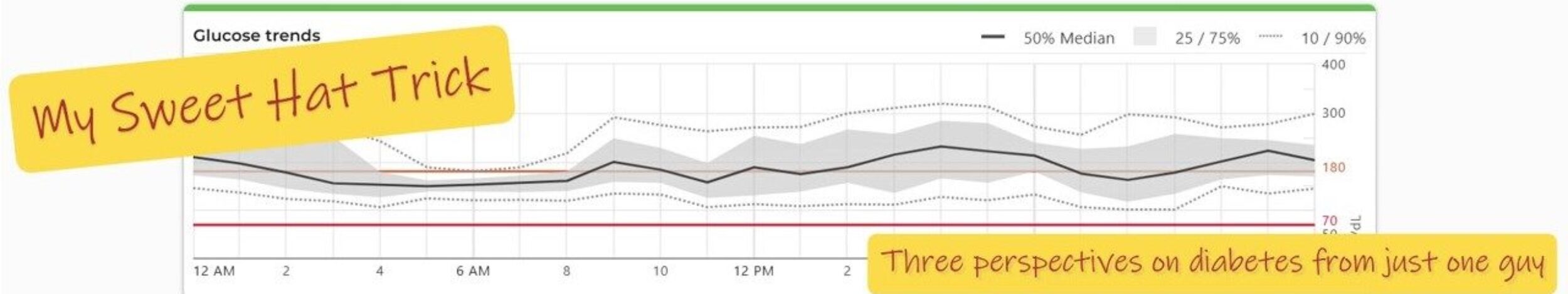

Coffee won’t be poured. Alarm clocks will still be threatening. Parents of kids with type 1 diabetes, myself included, may already be awake (but only half awake), checking a CGM graph glowing softly in the dark.

And in Livigno, Italy, Hannah Schmidt will be clicking into her skis.

Her Olympic morning begins with a seeding run in women’s ski cross, a sport built on speed, precision, and split-second decisions. It’s loud, aggressive, and unforgiving.

And Hannah is doing it all while managing type 1 diabetes.

From Diagnosis to the Start Gate

Hannah was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes at age 12.

At an age when most kids are navigating middle school and growth spurts, she was also learning insulin dosing, carbohydrate ratios, and how her body responded to exercise. She was already a multisport athlete at 12 and, according to Breakthrough T1D, participated in basketball, soccer, alpine skiing, and water sports, to name a few. She knew she wanted to compete in the Olympics, she just hadn’t decided in which sport.

She began specializing in Alpine skiing at 16, then moved on to ski cross at 18. From there, it was podiums, the World Cup, and eventually the Olympics (this will be her second appearance).

Diabetes did not remove her from competing at the highest level, but it did complicate it.

Training sessions became more than physical conditioning. They became experiments in glucose response. What happens to blood sugar during repeated sprint efforts? How does cold weather affect insulin absorption? How early should you fuel before a race start?

Those questions don’t show up on a results sheet, but they shape everything that follows.

The Sport That Looks Like Organized Chaos

If you’ve never watched ski cross, imagine this:

Four racers launch out of the start gate in an elimination-style race (two move on to the next round; two are eliminated). They drop into a steep descent, navigating rollers, tabletops, bermed turns, and sudden transitions, all while racing shoulder-to-shoulder toward the same finish line. What are rollers, tabletops, and bermed turns?

- Rollers are a series of rounded snow mounds that test rhythm and timing. Hit them wrong and you lose speed. Hit them right and you glide smoothly over the tops, conserving momentum.

- Tabletops are flat-topped jumps, built to launch athletes into the air before landing on the downslope. They require commitment. Hesitation costs distance and speed.

- Bermed turns are high, banked corners carved into the course, allowing racers to lean aggressively into the curve without losing control, like a snow-covered velodrome at 70 to 80 miles per hour.

Skis chatter. Snow sprays. Lines are defended. Space disappears quickly.

One mistake, a mistimed jump, a missed edge, a split-second hesitation, can mean elimination, or even a spectacular crash.

Ski cross looks chaotic.

It isn’t.

It’s choreography disguised as adrenaline.

Every move is calculated. Every push out of the start gate is rehearsed. Every line through a turn is chosen deliberately. Success requires physical power, timing, anticipation, and the ability to regulate emotion under pressure.

And now add another layer, glucose management.

The Invisible Race Within the Race

Type 1 diabetes does not pause for podiums.

High-intensity efforts can cause glucose to rise quickly. Adrenaline and competition stress can push it higher. Cold temperatures can influence insulin absorption and device performance. Fueling has to be timed. Insulin adjustments must anticipate not just the next run, but the recovery window between heats.

On February 20th, Hannah’s Olympic schedule will be as rapid as her races. A total of thirty-two women have qualified and will participate in ski cross:

- 4:00 a.m. EST – Seeding run (decides heat placement)

- 6:00 a.m. EST – Finals (eight rounds of four; 16 eliminated)

- 6:35 a.m. EST – Quarterfinals (four rounds of four; eight eliminated)

- 6:54 a.m. EST – Semifinals (two rounds of four)

- 7:10 a.m. EST – Small Final (those eliminated in the semis; decides 5th–8th place)

- 7:15 a.m. EST – Big Final (semifinal winners; decides 1st–4th place)

Multiple maximal efforts within just a few hours. Each round requires recalibration.

For most athletes, that means reviewing splits and course lines. For Hannah, it likely also means reviewing glucose trends, considering small adjustments, and ensuring stability before stepping back into the start gate. She relies on a Medtronic insulin pump with an integrated glucose sensor, which lets her monitor real-time trends and make adjustments on the fly, even while flying down the course at 80 mph.

But that balance isn’t accidental. It’s trained. Living with type 1 diabetes builds pattern recognition. It builds the habit of anticipating variables and adjusting quickly. It requires constant awareness, not panic, but steady attention.

In ski cross, hesitation costs speed. In type 1 diabetes, hesitation can cost stability.

Both reward preparation.

Competing With, Not Despite

It’s easy to tell stories about athletes succeeding “despite” a diagnosis.

But that framing misses something. Hannah is not competing in ski cross despite type 1 diabetes.

She’s competing with it.

It is integrated into her training, her race-day routines, and her preparation as an elite athlete. She has spoken openly about living with type 1 diabetes, serving as an ambassador for T1D Canada and using her platform to normalize what high-performance diabetes management looks like.

For young athletes like my son, especially those checking a CGM like Hannah does, visibility matters. It shifts the narrative from limitation to logistics.

Seeing someone launch off an Olympic jump while wearing the same technology they do changes the story.

Not “Can I?”, but “How do I?”

There is power in seeing someone navigate banked turns at 80 miles per hour while managing the same condition that requires you to carry glucose tabs in your backpack.

The Mental Game

Ski cross isn’t just physically demanding; it’s mentally relentless.

You are racing directly against other competitors. You must anticipate their moves, defend your line, and commit fully to your own. There’s no time for doubt once the gate drops.

Managing type 1 diabetes adds another mental layer. Data streams in constantly. Numbers require interpretation. Decisions require confidence. It would be easy to assume that this is an extra burden.

But it may also be a form of training.

Living with type 1 diabetes builds pattern recognition. It builds resilience. It builds the habit of assessing, adjusting, and moving forward, multiple times a day, every day.

Those skills translate.

When you’re standing in a start gate at the Olympics, composure matters. And composure is built through repetition.

High Speed. High Stakes. High Precision

Ski cross is fast. Aggressive. Unforgiving. Type 1 diabetes is persistent. Data-driven. Relentless.

Together, they demand an extraordinary level of balance.

On February 20, when the gate drops, all the world will see is speed. What it won’t see are the calculations made before dawn. The fueling decisions. The insulin timing. The quiet confidence that comes from knowing you’ve prepared not just for the course, but for your own physiology.

That’s the invisible discipline behind the visible performance. Whether Hannah stands on the podium or not, that balance is already remarkable.

If you want to learn more about Hannah, you can check out Canada’s Olympic Team Page at T1D or at OttawaSportsPages.ca