It was bound to happen.

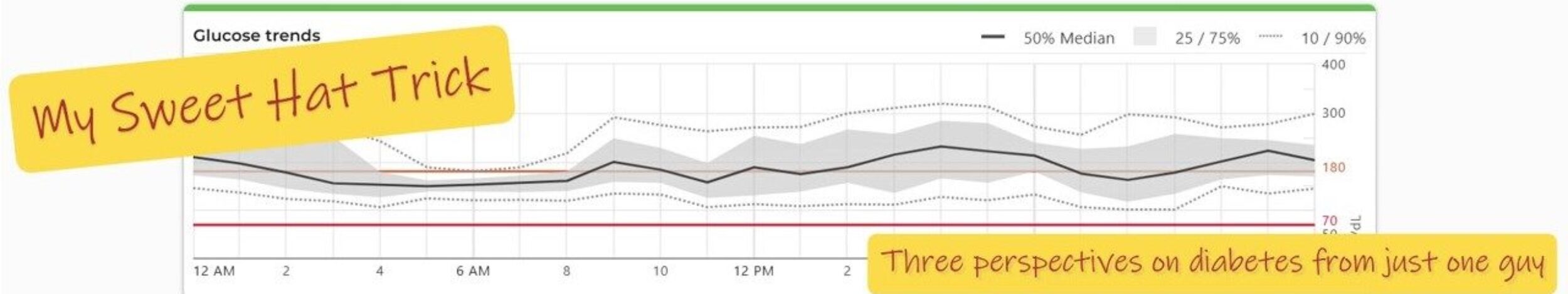

Life with three kids is about as predictable as a puppy on espresso, and type 1 diabetes hates unpredictability. Still, when Owen’s continuous glucose monitor (CGM) flashed that first screaming-red HIGH since his diagnosis, my stomach turned like it never had before.

I used to think having a high blood sugar myself was the worst I could ever feel.

I was wrong.

Pregame jitters—and sugar

Saturday started with a soccer game. Soccer means adrenaline, and adrenaline means rising blood glucose. Add a Frost Glacier Freeze Gatorade (because “electrolytes,” Dad!) and we had the perfect recipe for a spike.

Normally in a situation like this, I’d give a full correction bolus for the Gatorade and call it a day—I’m not ready to calculate the adrenaline factor yet. But the minute the final whistle blew, we had to hustle 25 minutes south for a birthday party. Owen would be running wild there, so I hesitated to front-load insulin.

He already had one unit on board, and I knew the pump was itching to deliver an auto-correction. I overrode it with a manual bolus—just 25% of the suggested dose—and encouraged him to drink some water on the ride. I hoped the wheels would stay on.

The ride of doom

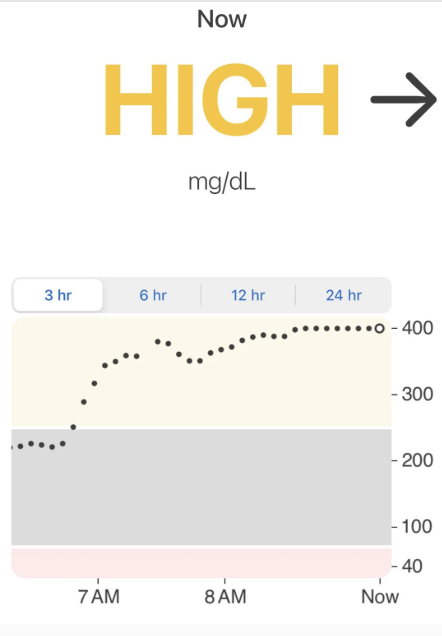

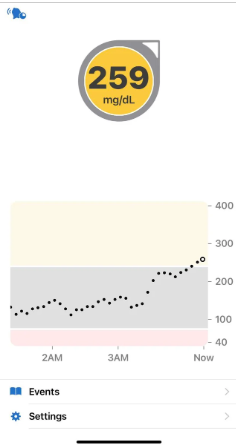

They didn’t. By the time we pulled into the party, Owen’s CGM read 259 mg/dL with one arrow up. Ten minutes later: 350 mg/dL—but flat.

I took a quick blood glucose reading to confirm, an important first step when you’re dealing with a high. I wish I’d packed his blood ketone meter, but I hadn’t—a good lesson for next time.

I checked the pump: no occlusions, no alarms. I had a backup set ready to go, but based on what I saw, I didn’t think it was needed. Owen’s tubing is completely hidden under his clothes when he plays soccer, so I knew it likely hadn’t gotten pulled—but I still spot-checked his infusion site. It looked fine: no moisture, no smell of insulin.

Based on all of that, I concluded this was the perfect storm of sport, sugar, and stress—not an insulin delivery issue.

I knew the party was in a park, so I crossed every finger for a bit of activity. Turns out the first 45 minutes were flag football, and in most cases, exercise is insulin’s best friend. I was a little concerned the intensity might spike him even more, but I made a judgment call based on the information I had. I gave another conservative manual correction—just enough to delay the pump’s auto-correction—and sent him onto the field, quietly praying.

Watching the climb

Here’s the cruel thing about diabetes: having a high feels awful, but watching your child have one feels worse.

Twenty years ago, I took part in a sensor accuracy study in Philadelphia with Dr. Jeffrey Joseph. I started with a blood sugar in range. They nudged me up to 250 mg/dL, then had me ride a stationary bike to bring it back down.

Dr. Joseph pointed out how my eyes sank, my shoulders slumped—and how I “came back to life” as my blood sugar dropped. No video exists, but that memory played in HD on Saturday.

Owen—my endlessly outgoing kid, the one who gets a chorus of goodbyes from every grade level at dismissal—looked gray around the eyes. On the field, he faded from sprinting to jogging to drifting, barely lifting a hand for the ball.

The Dexcom Follow app alarmed that his glucose was now HIGH, and it was time to pivot. I pulled him aside for more water—and an urgent bathroom trip (thanks, high blood sugar). By the time we returned, his blood glucose was finally starting to come down. The game ended just as we rejoined, and I silently rejoiced.

I bolused for a full correction—plus two slices of pizza and a slab of birthday cake.

Biggest dose of his short life.

The crash—and the comeback

Party over, Owen folded into the back seat like a deflated beach ball. At home, he slumped on the couch for almost two hours while the insulin did its work.

Then, right on schedule, the CGM traced a gentle glide back to target. Color returned to his cheeks, and my kid popped up like someone hit “resume” on his energy.

The debrief

I’m grateful I didn’t give too much insulin and cause a crash at the party. But maybe 25% of the recommended bolus wasn’t enough.

And having the blood ketone meter—or at least ketone strips—would’ve been good to have. Even educators make mistakes.

This disease can be a thief—it stole my kid’s spark for a few hours—but it also makes us tougher, smarter, more prepared.

One high, one lesson.

On to the next game.

For tips on what to do when your child has a high blood sugar, click the PDF logo