Starting the Journey

I thought I’d kick things off by starting with what really got me here.

No, not my diagnosis — that’s what pushed me toward working in diabetes. I mean, what got me here, stepping out of my comfort zone and trying out this whole writing thing (because clearly what the world needs is another dad with opinions and a Wi-Fi connection). I’m talking about Owen’s diagnosis.

Facing Uncertainty

I was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes when I was seven. A lot has changed since then — in what we know about the disease, how we can delay it, and how we treat it once diagnosed. I’m grateful for the advancements that have kept me healthy and complication-free for the last 45 years. I feel confident living with diabetes. I don’t think I fear the disease itself anymore — except for one thing:

Passing it on to my kids.

Mind you, I was diagnosed when I was seven. And after years of wondering, would they or wouldn’t they? — as in, would my kids be diagnosed too — I guess I had used that the age I was diagnosed as some kind of goalpost. I’d been worried about whether any of my kids would develop diabetes since the day they were born. But after each of them hit age eight, my mind needed a break. I basically declared us in the diabetes-free zone and moved on — like a dad who thinks one good cholesterol result means he can eat bacon again.

And then came the signs. Yes, those signs.

The ones his mother and I know by heart. But in the chaos of co-parenting from two separate homes, we just didn’t see them.

Owen was always skinny, so weight loss didn’t register. Increased thirst and hunger? Hard to tell with three kids — dinner time is like feeding time at the zoo. (If the zookeepers were understaffed and the animals had opinions about the mac and cheese.) But then there was the bedwetting. That was the one. That was the sign.

Like most kids, he had the occasional accident. I didn’t think too much of it. But I do remember noticing it was happening more often. Then came a week where he wet the bed every night — and then twice in one night. It didn’t register at the time; I was washing two sets of sheets while getting three kids out the door and myself to work. It wasn’t until I was leaving the office that the realization hit me.

The Moment of Truth

By the time I got home, the kids were with their sitter. I called a friend down the street to come over for moral support while I checked Owen’s blood sugar.

HI.

That’s what the meter read — blood sugar too high to measure. I had him wash his hands again (he had already done so the first time, but this time I supervised and rechecked). I stepped back, afraid to look. He peeked at the screen, turned it toward me, and said:

“Well, HI to you too!”

If the situation had been different, I might’ve given him a high five for comedic timing.

Rushing to the Hospital

I left my two older kids with the neighbor and took off for the hospital where I worked — figured that might help us get through the ER quicker. I called his mom on the way, and she redirected me immediately to Nemours, the children’s hospital just south of us. Thank goodness she did. My hospital had a pediatric wing, but Owen would’ve been transferred to a children’s hospital anyway.

And so, on the evening of Friday, June 9, 2023, we piggybacked our way from the parking lot to the ER. A quick glucose and ketone test confirmed the diagnosis.

Thankfully, Owen wasn’t in DKA — a dangerous condition that unfortunately is how many Type 1s are diagnosed. Since it was a Friday, we wouldn’t be able to meet with the endocrinology team before discharge, so we’d have to stay the weekend.

A Different Experience

Owen had it pretty good, to be honest. Brightly colored room, his own TV, Xbox, and a room service-style menu he could order from any time. I was so jealous. I started wondering if I could fake low blood sugar and sneak a waffle off his tray.

Not that this is a competition, but when I was diagnosed, it was in a “big boy” hospital — the adult kind. My room color was some weird “industrial yellow,” the food looked like it had been boiled for safety, and I had to share a room with a 70-year-old man who kept yelling at me for touching the remote. (To be fair, I was seven. Seven-year-olds and 70-year-olds should not be roommates.)

A Quiet Realization

That night, I took a walk around the hospital floor. It was quiet, dimly lit, and most doors were open. I didn’t look inside, but I could hear the machines. You can tell a lot about a patient’s condition by the number of beeps coming from the room.

That’s when it hit me: Owen is going to be fine.

I never thought I’d say this — me having diabetes is an advantage.

Tools, Support, and Hope

I have diabetes. His mom and I are both diabetes educators. We’ve worked in the diabetes industry and still know many people who do. His godmother is an insulin pump trainer. And the tools we have today — sensor-augmented insulin pumps — are the stuff I used to dream about when I was his age.

Yes, there will be a learning curve, but it will be shorter.

And yes, I never thought I’d say this — me having diabetes is actually an advantage.

Back to Normal (Almost)

The next day, he had visitors. His siblings and mom arrived first, and within ten minutes, the kids were arguing over what to order from the menu — music to my ears. Then his best friend came, jumped into bed with him, and asked if he could make the legs go up and down. It was almost… normal again.

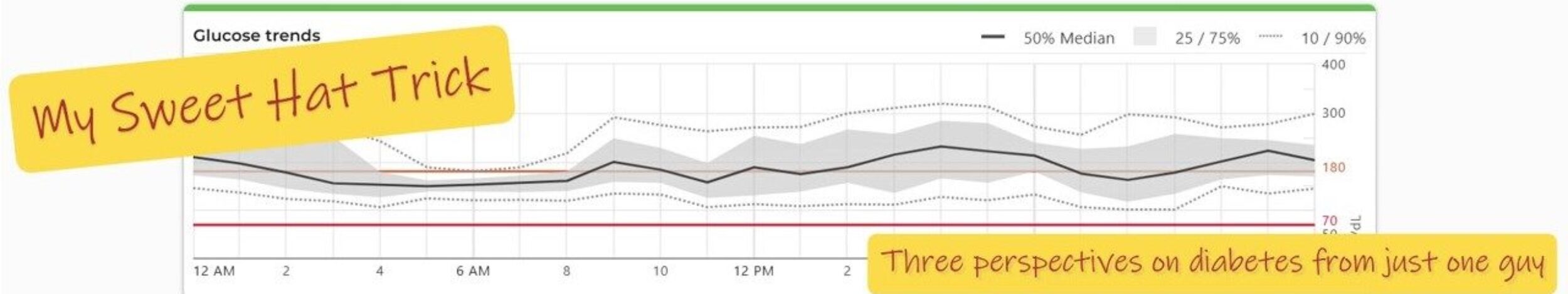

On Monday, we met the endocrinology team. We left the hospital with a Dexcom sensor and a script for a Tandem T: Slim insulin pump — which he’d later be trained on by his godmother, of course.

This won’t be easy. Diabetes is a part of our lives now, and it will bring its challenges. But we are incredibly lucky.

And most of all — Owen is going to be just fine.

Photo Credits: Cartoons were designed at AIEASE. The HI image was found at Accu-Chek