When Owen is ready, there’s something important I want him to know—something I still wrestle with myself. The word “diabetic” gets used a lot. Some say it casually, others with concern or care, and many without much thought. But language matters. And how he chooses to feel about it is entirely up to him.

<!-- wp:verse -->

<pre class="wp-block-verse"><strong>Yes, I’m diabetic. But I’m also athletic, artistic, empathetic, dynamic, eccentric, charismatic, iconic (at least in my own mind)—and, on rare occasions when I write, I’m even a little comedic. </strong></pre>

<!-- /wp:verse -->

And no, this isn’t about being overly sensitive—or not sensitive at all. It’s about identity, dignity, and the power of words to shape how others see us and how we see ourselves. This issue matters not just because of Owen. My oldest son is on the autism spectrum and will face similar challenges with language and identity.

The Word “Diabetic”

The word “diabetic” has been around for a long time—probably as long as we’ve had the word diabetes. It was likely coined by the medical community, and up until a few years ago, it was used in all types of communication. Often, it’s just a shorthand: “She’s a diabetic.” “The diabetic diet.” “He’s a Type 1 diabetic.”

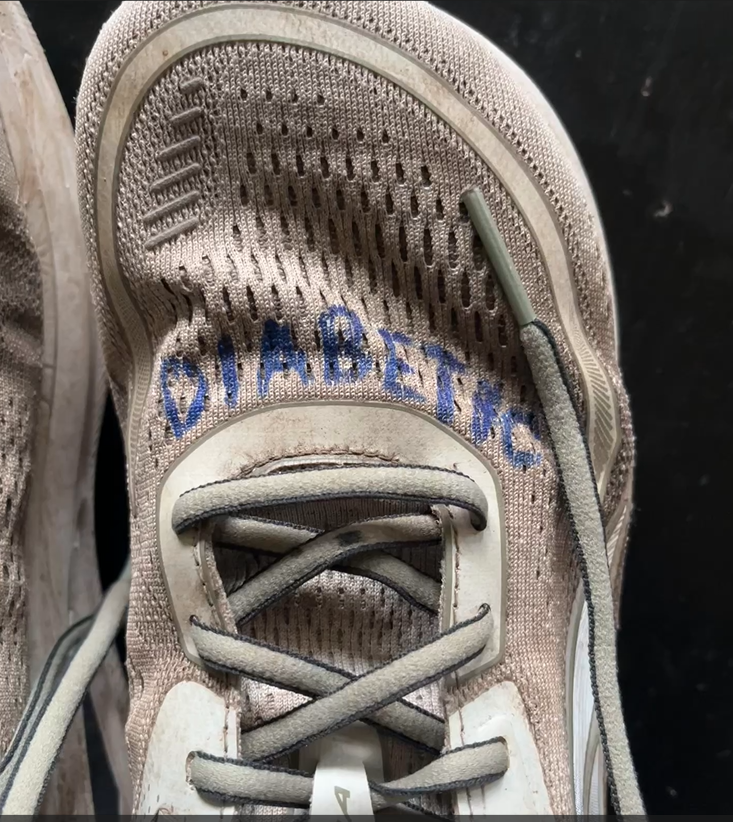

My first medical alert necklace had “Type 1 Diabetic” on it. I’d worn a necklace like that since I was seven. It felt like my lifeline—my safety net. But at my first cross-country meet as a junior, the officials told me I had to take it off. Their rules didn’t allow jewelry during competition. I refused. My coach was yelling—at them, at me. So I grabbed a Sharpie from one of the officials and wrote the word “diabetic” on my racing flats.

It became a badge of honor. To me, it said: I have diabetes, and I’m still going to kick your ass. (Sorry for the language, Mom.) I liked it so much, I eventually got it tattooed on my arm in college.

Years later, when I worked my first diabetes camp, I was surprised when the camp director, Alecia McAuliffe (whom I still consider a cherished friend), asked me to cover my tattoo. At first, I was stunned—they had invited me to give a talk about not letting diabetes hold you back, and now they wanted me to hide what made me proud.

But she explained—and rightly so—that for some campers, that label “diabetic” can feel limiting. It can become the lens through which the world sees them. And that lens can shrink a complex, vibrant person down to just a diagnosis. It blew my mind, and I’m so glad I learned this from her when I did.

Rachel Morgan wrote an excellent piece about this for Beyond Type 1, Diabetic vs. Diabetes. Rather than paraphrasing her thoughts, I encourage you to read her article—it offers thoughtful context that pairs well with what I share here.

Identity-First vs. Person-First Language

In healthcare and advocacy, there’s been an ongoing conversation about identity-first versus person-first language.

- Identity-first language puts the condition first: “diabetic.”

- Person-first language puts the person first: “person with diabetes.”

Why does this matter? Because the way we speak reflects how we think. Saying “a person with diabetes” reinforces that diabetes is something a person has—not all that they are. It separates the individual from the illness. It acknowledges their humanity first.

Many people with diabetes prefer this approach because it feels more respectful, more accurate, and more empowering.

Why It Matters

Language isn’t just about words—it’s deeply personal. It shapes how people feel about themselves, especially in childhood and adolescence, when identity is still forming. For a young person growing up with diabetes, being called “a diabetic” again and again can feel like their whole self is being reduced to their condition.

I’ve seen this firsthand—in education sessions, in support groups, and even in casual conversation. When people hear themselves defined by a diagnosis, it can lead to internalized stigma, shame, or a sense of being “less than.” And for those who don’t live with diabetes, the language can unconsciously reinforce bias—framing people as their disease, rather than as individuals living with it.

Compassion and Context

That said, not everyone who uses the word “diabetic” means harm. In fact, most people don’t. They’re using the language they’ve heard their whole lives—language that, for a long time, was even considered medically appropriate.

I doubt my neighbor meant anything negative when she said, “I’m so sorry your son is diabetic.” It was actually a great opportunity to gently explain that we now prefer “person with diabetes.”

That’s something I want my son to understand, too. The goal isn’t to police people’s words or judge their intentions. It’s to open the door to better conversations—ones that help us choose words that affirm, not reduce.

Compassion works both ways: compassion for the person with diabetes, and compassion for the person still learning how to talk about it.

The Way I’ve Always Seen It

But here’s a question I’ve asked myself many times: is diabetic a definition, or a description?

Yes, I’m diabetic. But I’m also athletic, artistic, empathetic, dynamic, eccentric, charismatic, iconic (at least in my own mind)—and, on rare occasions when I write, I’m even a little comedic.

I’ve never heard LeBron James say, “I don’t want to be labeled as athletic—I’m more than that.” (Maybe he has—but let’s roll with it.) When a label feels like a compliment, it’s easier to embrace. And for me, diabetic has always carried a positive charge. It speaks to resilience, awareness, strength.

Letting My Son Decide

His words will be his own.

He gets to decide how he identifies, what language he uses, and how he wants to be seen. If one day he proudly says, “I’m a diabetic,” that’s his choice. If he prefers “person with diabetes,” that’s his right, too. Either way, I’ll be proud of him.

What matters most is that he knows he has a choice. That words carry meaning. And that his voice—and his experience—deserve to be at the center of how he’s seen and heard.

A Final Thought

To anyone reading this—whether you live with diabetes, love someone who does, or work in a space where language matters—I invite you to reflect.

Ask yourself what words you use, and why. Ask others what they prefer. And when in doubt, lead with respect, curiosity, and care.

Words are powerful. But they don’t define us. The people who live beyond them do.